Summary: A new study reveals flexibility and modularity are negatively correlated in the brain.

Source: Rice University.

A new study by Rice University researchers takes a step toward what they see as key to the advance of neuroscience: a better understanding of the relationship between the brain’s flexibility and its modularity.

Their open-access study appears in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

Scientists are only beginning to comprehend how brains are wired, both structurally and functionally. The latest in a series of studies by Rice scientists shows that the brain’s flexibility and modularity – which researchers often study independently – are strongly related. The new study also presents a theoretical framework to explain the two processes.

They found that flexibility, which relates to how much brain networks change over time, and modularity, which defines the degree of interconnectivity between parts of the brain responsible for specific tasks, are highly negatively correlated. In other words, people with highly modular brains that constrain tasks to the modules also show low flexibility, while people with high-flexibility brains that share tasks across the network show low modularity.

These properties explain how participants perform in experiments, according to co-author and Rice psychologist Simon Fischer-Baum. When someone is presented with a complex task, flexibility of the brain network better explains performance than the modularity of the network. For a simple task, he said, the reverse is true, which indicates that these ways of thinking about brain organization map onto different cognitive abilities.

But even that sliding scale only hints at the relationship between flexibility and modularity.

“There have been a bunch of papers about the flexibility of the network and how that relates to cognition and a bunch of other papers about modularity and its relation to cognition, but nobody’s really explored whether these things are tapping into different aspects of cognition or if they’re two sides of the same coin,” said Fischer-Baum, who was the lead faculty member on the study in collaboration with Rice psychologist Randi Martin and biophysicist Michael Deem.

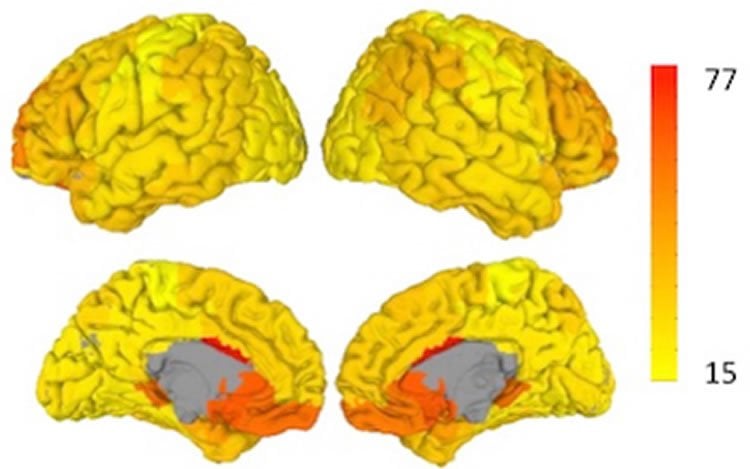

“People can be described in terms of how flexible their brain networks are: how frequently brain regions change the modules they’re assigned to or how stable the modules stay over time,” Fischer-Baum said. Regions of the brain with higher flexibility are those typically associated with cognitive control and executive function, the processes that control behavior. Regions with lower flexibility are those involved in motor, taste, vision and hearing processes.

The researchers took two paths to map the modules and thought processes of 52 subjects ranging in age from 18 to 26; 31 percent of the participants were male and 69 percent were female.

First, the subjects underwent resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which detected blood oxygen levels to track activity and measure modularity (the likelihood of connections within modules of the brain) and flexibility (how frequently regions switch allegiance from one module to another).

Second, the subjects took a battery of six cognitive tests to assess their performance on simple and complex tasks.

Data from both paths had previously been used to show that brain modularity correlates positively with performance on simple tasks and negatively with performance on complex tasks. The question that remained was how modularity relates to other measures of network organization, like flexibility, and how flexibility relates to cognitive processing as a whole. The goal of the Rice study was to analyze the entire brain network rather than individual components.

“Cognition is complex,” Fischer-Baum said. “Any task relies on multiple areas of the brain doing different functions and communicating with each other. We have to be able to articulate why, for a given task, it’s good to have a particular type of brain organization.”

Participants were given a series of common cognitive psychology experiments, which yielded composite scores for simple and complex behaviors that aligned with the fMRI results. Participants who showed high flexibility fared best on complex tests that required the ability to quickly switch between tasks and draw upon working memory. One, for example, presented them a square or triangle in blue or yellow and required the participants to respond to a cue about either the color or shape of the object.

Those who scored higher on the modular scale excelled on tasks with more limited behavioral requirements, like a traffic-light test that required them to hit a button as quickly as possible when they saw a light turn from red to green and measured their response times.

The researchers noted it would be incorrect to think that modularity and flexibility simply measure the same property. Because they make independent contributions to performance, the researchers theorize they are “likely to link to different cognitive processes.”

They also theorized that learning a skill may account for variation within individuals between modularity and flexibility. The researchers wrote that during the initial stages of learning, even a simple skill may employ cognitive controls usually required for complex tasks. But as the task is learned and becomes simpler, flexibility decreases and modularity increases.

“This broad division between complex and simple tasks is a first pass at the problem,” he said. “It’s not just that having a modular brain is good, or having a flexible brain is good. We want to know what they’re good for and the timescales at which these variables have an impact.”

Aurora Ramos-Nuñez, a former research scientist in the Fischer-Baum lab and now an assistant professor of psychology at the College of Coastal Georgia, is lead author of the paper. Co-authors are Rice graduate students Qiuhai Yue and Fengdan Ye. Martin is the Elma Schneider Professor of Psychology. Deem is the John W. Cox Professor of Biochemical and Genetic Engineering and a professor of physics and astronomy. Fischer-Baum is an assistant professor of psychology.

Funding: The T.L.L. Temple Foundation and the National Science Foundation-supported Center for Theoretical Biological Physics at Rice funded the research.

Source: Mike Williams – Rice University

Publisher: Content organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is adapted from the Rice University news release.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Static and Dynamic Measures of Human Brain Connectivity Predict Complementary Aspects of Human Cognitive Performance” by Aurora I. Ramos-Nuñez, Simon Fischer-Baum, Randi C. Martin, Qiuhai Yue, Fengdan Yeand Michael W. Deem in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. Published online August 242017 doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00420

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Rice University “Tangled Up in Gray: Shifting Relationship Between Flexibility and Modularity in Brain Discovered.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 19 October 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/modularity-flexibility-neuroscience-7768/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Rice University (2017, October 19). Tangled Up in Gray: Shifting Relationship Between Flexibility and Modularity in Brain Discovered. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved October 19, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/modularity-flexibility-neuroscience-7768/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Rice University “Tangled Up in Gray: Shifting Relationship Between Flexibility and Modularity in Brain Discovered.” https://neurosciencenews.com/modularity-flexibility-neuroscience-7768/ (accessed October 19, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Static and Dynamic Measures of Human Brain Connectivity Predict Complementary Aspects of Human Cognitive Performance

In cognitive network neuroscience, the connectivity and community structure of the brain network is related to measures of cognitive performance, like attention and memory. Research in this emerging discipline has largely focused on two measures of connectivity—modularity and flexibility—which, for the most part, have been examined in isolation. The current project investigates the relationship between these two measures of connectivity and how they make separable contribution to predicting individual differences in performance on cognitive tasks. Using resting state fMRI data from 52 young adults, we show that flexibility and modularity are highly negatively correlated. We use a Brodmann parcellation of the fMRI data and a sliding window approach for calculation of the flexibility. We also demonstrate that flexibility and modularity make unique contributions to explain task performance, with a clear result showing that modularity, not flexibility, predicts performance for simple tasks and that flexibility plays a greater role in predicting performance on complex tasks that require cognitive control and executive functioning. The theory and results presented here allow for stronger links between measures of brain network connectivity and cognitive processes.

“Static and Dynamic Measures of Human Brain Connectivity Predict Complementary Aspects of Human Cognitive Performance” by Aurora I. Ramos-Nuñez, Simon Fischer-Baum, Randi C. Martin, Qiuhai Yue, Fengdan Yeand Michael W. Deem in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. Published online August 242017 doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00420