Researchers at the University of Bonn identify an important neuronal mechanism.

Researchers from Germany and the USA have identified an important mechanism with which memory switches from recall to memorization mode. The study may shed new light on the cellular causes of dementia. The work was directed by the University of Bonn and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE). It is being published in the renowned journal Neuron.

Because of its shape, the control center of memory bears the poetic name of “hippocampus” (seahorse). New sensations to be stored continually enter this region of the brain. But at the same time, the hippocampus is also the guardian of memories: It retrieves stored information from the depths of memory.

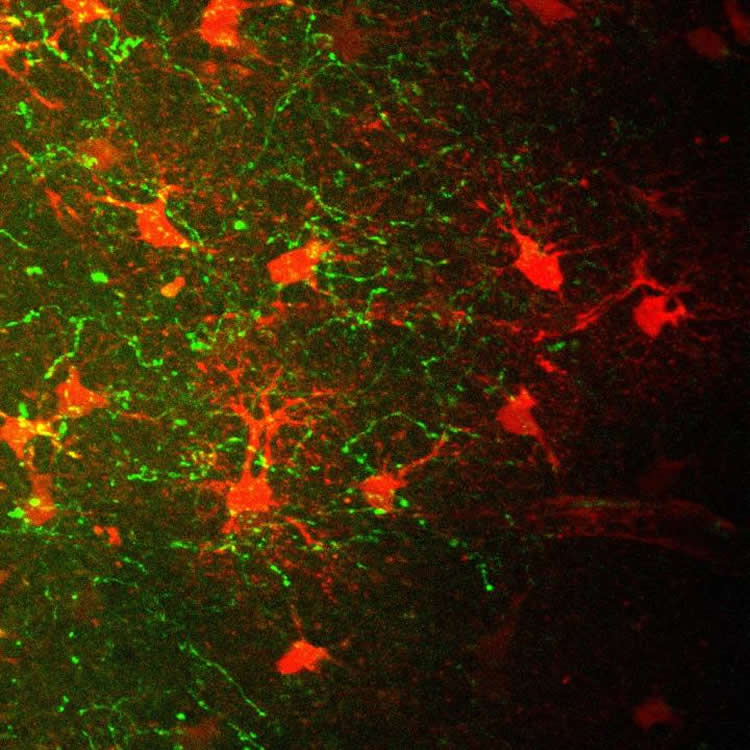

The hippocampus is also an important transport junction. And just like rush hour in a major city, it also needs a regulating hand to control the opposing flows of information. The researchers from Bonn, Los Angeles and Palo Alto have now identified such a memory traffic policeman. Certain cells in the brain, the hippocampal astrocytes, ensure that the new information is given priority. The mind thus switches into memorization mode; by contrast, the already saved memories must wait.

However, the astrocytes themselves only take orders: They react to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is released in particular in novel situations. It has been known for several years that acetylcholine promotes the storage of new information. How this happens has only been partly understood. “In our work, we were able to show for the first time that acetylcholine stimulates astrocytes which then are induced to release the transmitter glutamate,” explains Milan Pabst, who is a doctoral candidate at the Laboratory for Experimental Epileptology of the University of Bonn. “The released glutamate then activates inhibitory nerve cells which inhibit a pathways mediating the retrieval of memories.”

The researchers working with the neuroscientist PDr. Heinz Beck genetically modified nerve cells so that they could be activated by light and then release acetylcholine. Using this trick, they were able to clarify the mechanism using recordings in living brain tissue sections. “However, we also show that, in the brains of living mice, acetylcholine has the same effect on the activity of the neurons,” explains Pabst’s colleague, Dr. Holger Dannenberg.

Astrocytes have long since been underestimated

Another reason this result is interesting is because astrocytes themselves are not nerve cells. They belong to what are known as glial cells. Until the turn of the millennium, they were still considered to merely serve as mechanical support to the real stars of the brain, the neurons.

In recent decades, however, it has become increasingly clearer that this image is far from correct. It is known by now that astrocytes can release neurotransmitters – the messengers by which neurons communicate with each other — or even remove them from the brain. “It was previously unknown that the astrocytes are involved in central memory processes through the mechanism which has now been discovered,” explains Prof. Beck. However, an observation made by US scientists in 2014 fits into this context: If astrocytes’ function is inhibited, this has a negative effect on the recognition of objects.

The results may also shed new light on the cellular causes of memory disorders. Thus there are indications that the controlled secretion of acetylcholine is disrupted in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. “However, we have not investigated whether the mechanism we discovered is also impacted,” stresses Pabst.

Source: Dr. Heinz Beck – University of Bonn

Image Credit: The image is credited to Milan Pabst & Oliver Braganza/University of Bonn.

Original Research: Abstract for “Astrocyte Intermediaries of Septal Cholinergic Modulation in the Hippocampus” by Milan Pabst, Oliver Braganza, Holger Dannenberg, Wen Hu, Leonie Pothmann, Jurij Rosen, Istvan Mody, Karen van Loo, Karl Deisseroth, Albert Becker, Susanne Schoch, and Heinz Beck in Neuron. Published online May 5 2016 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.003

Abstract

Astrocyte Intermediaries of Septal Cholinergic Modulation in the Hippocampus

Highlights

•Cholinergic modulatory inputs cause slow inhibition of hippocampal granule cells

•This slow inhibition is mediated via astrocytic intermediaries

•Acetylcholine released from septohippocampal projections activates astrocytes

•Astrocytes excite hilar interneurons, causing granule cell inhibition

Summary

The neurotransmitter acetylcholine, derived from the medial septum/diagonal band of Broca complex, has been accorded an important role in hippocampal learning and memory processes. However, the precise mechanisms whereby acetylcholine released from septohippocampal cholinergic neurons acts to modulate hippocampal microcircuits remain unknown. Here, we show that acetylcholine release from cholinergic septohippocampal projections causes a long-lasting GABAergic inhibition of hippocampal dentate granule cells in vivo and in vitro. This inhibition is caused by cholinergic activation of hilar astrocytes, which provide glutamatergic excitation of hilar inhibitory interneurons. These results demonstrate that acetylcholine release can cause slow inhibition of principal neuronal activity via astrocyte intermediaries.

“Astrocyte Intermediaries of Septal Cholinergic Modulation in the Hippocampus” by Milan Pabst, Oliver Braganza, Holger Dannenberg, Wen Hu, Leonie Pothmann, Jurij Rosen, Istvan Mody, Karen van Loo, Karl Deisseroth, Albert Becker, Susanne Schoch, and Heinz Beck in Neuron. Published online May 5 2016 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.003