As recovering spring breakers are regretting binge drinking escapades, it may be hard for them to appreciate that there is a positive side to the nausea, sleepiness, and stumbling. University of Utah neuroscientists report that when a region of the brain called the lateral habenula is chronically inactivated in rats, they repeatedly drink to excess and are less able to learn from the experience. The study, published online in PLOS ONE on April 2, has implications for understanding behaviors that drive alcohol addiction.

While complex societal pressures contribute to alcoholism, physiological factors are also to blame. Alcohol is a drug of abuse, earning its status because it tickles the reward system in the brain, triggering the release of feel-good neurotransmitters. The dreaded outcomes of overindulging serve the beneficial purpose of countering the pull of temptation, but little is understood about how those mechanisms are controlled.

U of U professor of neurobiology and anatomy Sharif Taha, Ph.D., and colleagues, tipped the balance that reigns in addictive behaviors by inactivating in rats a brain region called the lateral habenula. When the rats were given intermittent access to a solution of 20% alcohol over several weeks, they escalated their alcohol drinking more rapidly, and drank more heavily than control rats.

“In people, escalation of intake is what eventually separates a social drinker from someone who becomes an alcoholic,” said Taha. “These rats drink amounts that are quite substantial. Legally they would be drunk if they were driving.”

The lateral habenula is activated by bad experiences, suggesting that without this region the rats may drink more because they fail to learn from the negative outcomes of overindulging. The investigators tested the idea by giving the rats a desirable, sweet juice then injecting them with a dose of alcohol large enough to cause negative effects.

“It’s the same kind of learning that mediates your response in food poisoning. You taste something and then you get sick, and then of course you avoid that food in future meals,” explained Taha.

Yet rats with an inactivated lateral habenula sought out the juice more than control animals, even though it meant a repeat of the bad experience.

“The way I look at it is the rewarding effects of drinking alcohol compete with the aversive effects,” explained Andrew Haack, who is co-first author on the study with Chandni Sheth, both neuroscience graduate students. “When you take the aversive effects away, which is what we did when we inactivated the lateral habenula, the rewarding effects gain more purchase, and so it drives up drinking behavior.”

The group’s findings may help explain results from previous clinical investigations demonstrating that men who were less sensitive to the negative effects of alcohol drank more heavily, and were more likely to become problem drinkers later in life.

The researches think the lateral habenula likely works in one of two ways. The region may regulate how badly an individual feels after over-drinking. Alternatively, it may control how well an individual learns from their bad experience. Future work will resolve between the two.

“If we can understand the brain circuits that control sensitivity to alcohol’s aversive effects, then we can start to get a handle on who may become a problem drinker,” said Taha.

Funding support was provided by the National Institutes Health under award MH094870, the March of Dimes Foundation, and the University of Utah.

Contact: Julie Kiefer – University of Utah

Source: University of Utah press release

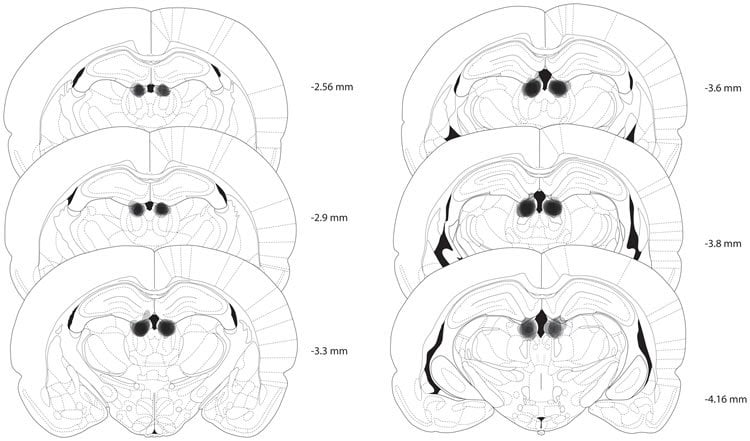

Image Source: The image is credited to Taha et al/PLOS ONE and is adapted from the open access research paper.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Lesions of the Lateral Habenula Increase Voluntary Ethanol Consumption and Operant Self-Administration, Block Yohimbine-Induced Reinstatement of Ethanol Seeking, and Attenuate Ethanol-Induced Conditioned Taste Aversion” by Andrew K. Haack, Chandni Sheth, Andrea L. Schwager, Michael S. Sinclair, Shashank Tandon, and Sharif A. Taha, for the Brain Institute in PLOS ONE. Published online April 2 2014 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092701

“Lesions of the Lateral Habenula Increase Voluntary Ethanol Consumption and Operant Self-Administration, Block Yohimbine-Induced Reinstatement of Ethanol Seeking, and Attenuate Ethanol-Induced Conditioned Taste Aversion”

The lateral habenula (LHb) plays an important role in learning driven by negative outcomes. Many drugs of abuse, including ethanol, have dose-dependent aversive effects that act to limit intake of the drug. However, the role of the LHb in regulating ethanol intake is unknown. In the present study, we compared voluntary ethanol consumption and self-administration, yohimbine-induced reinstatement of ethanol seeking, and ethanol-induced conditioned taste aversion in rats with sham or LHb lesions. In rats given home cage access to 20% ethanol in an intermittent access two bottle choice paradigm, lesioned animals escalated their voluntary ethanol consumption more rapidly than sham-lesioned control animals and maintained higher stable rates of voluntary ethanol intake. Similarly, lesioned animals exhibited higher rates of responding for ethanol in operant self-administration sessions. In addition, LHb lesion blocked yohimbine-induced reinstatement of ethanol seeking after extinction. Finally, LHb lesion significantly attenuated an ethanol-induced conditioned taste aversion. Our results demonstrate an important role for the LHb in multiple facets of ethanol-directed behavior, and further suggest that the LHb may contribute to ethanol-directed behaviors by mediating learning driven by the aversive effects of the drug.

Andrew K. Haack, Chandni Sheth, Andrea L. Schwager, Michael S. Sinclair, Shashank Tandon, and Sharif A. Taha, for the Brain Institute “Lesions of the Lateral Habenula Increase Voluntary Ethanol Consumption and Operant Self-Administration, Block Yohimbine-Induced Reinstatement of Ethanol Seeking, and Attenuate Ethanol-Induced Conditioned Taste Aversion” in PLOS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092701.