Skeleton that protects brain cells’ control center is found to be damaged.

Brain cell death in Alzheimer’s disease is linked to disruption of a skeleton that surrounds the nucleus of the cells, a researcher in the School of Medicine at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio said.

The finding is expected to open new avenues of study of how to prevent the earliest biological events that result in Alzheimer’s.

The nucleus is the control center of cells. A mesh-like scaffold called the lamin nucleoskeleton surrounds this control center but is disordered in Alzheimer’s, said Bess Frost, Ph.D., assistant professor of cellular and structural biology at the UT Health Science Center at San Antonio. Dr. Frost was trained at Harvard Medical School and in November started her new laboratory at the UT Health Science Center’s Barshop Institute for Longevity and Aging Studies.

Confirmed in human cells

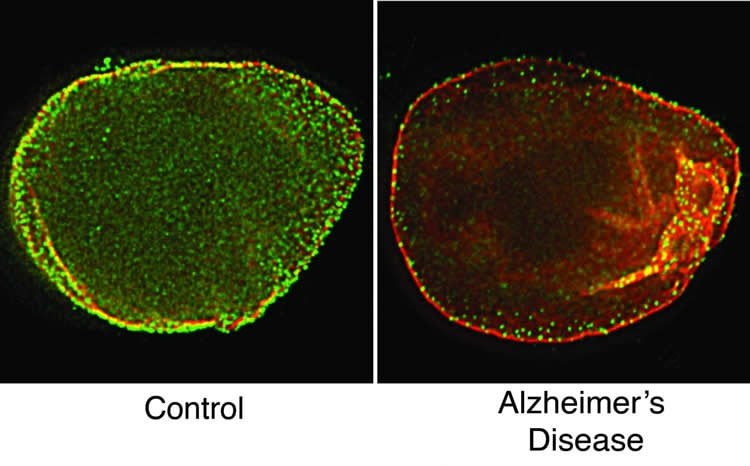

Dr. Frost and two co-authors showed–for the first time–that lamin dysfunction can cause the death of brain cells, which are called neurons. The team made this finding in a fruit fly disease model initially and confirmed it in postmortem brain tissue of people who had Alzheimer’s disease, whose families donated their brains to research.

“Human brain donation is a very critical part of this work,” Dr. Frost said. “It was important to show that what we found in the fly is really relevant to human disease.”

Dr. Frost and her colleagues used a technique called super-resolution microscopy to analyze the fruit fly and human specimens. They found peculiar features that looked like tunnels in the lamin of Alzheimer’s-affected specimens.

Seems to be Alzheimer’s-specific

The team also studied a fruit fly model of Huntington’s disease and did not find any problems with the lamin. “So, at least compared to one other neurodegenerative disease, lamin dysfunction seems to be specific to Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Frost said.

The findings, made while Dr. Frost was at Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, are in in the journal Current Biology and were posted online in January.

Dr. Frost encourages people to consider brain donation, whether or not they have a neurodegenerative disease. Comparing healthy, normal brain tissue to diseased brain tissue is a very useful tool for neuroscientists, she said.

New Alzheimer’s institute

A state-of-the-art tissue biorepository will be part of the Institute for Alzheimer and Neurodegenerative Diseases announced by the Health Science Center last September. The biobank will be linked to a database containing the health history of each donor.

Dr. Frost said she is very excited that the institute is being launched and plans to be involved once it is operational. Dr. Frost is establishing her laboratory with support from The University of Texas System Rising STARS Award. STARS stands for Science and Technology Acquisition and Retention.

Source: Will Sansom – UT Health Science Center San Antonio

Image Credit: The image is credited to Laboratory of Bess Frost, Ph.D./UT Health Science Center San Antonio

Original Research: Abstract for “Lamin Dysfunction Mediates Neurodegeneration in Tauopathies” by Bess Frost, Farah H. Bardai, and Mel B. Feany in Current Biology. Published online December 24 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.039

Abstract

Lamin Dysfunction Mediates Neurodegeneration in Tauopathies

Highlights

•Disruption of the lamin nucleoskeleton drives neuronal death in tauopathy

•Lamin dysfunction causes heterochromatin relaxation and cell death in neurons

•Improper cytoskeletal/nucleoskeletal coupling disrupts lamin in tauopathy

•Lamin pathology is conserved in postmortem human Alzheimer’s disease brains

Summary

The filamentous meshwork formed by the lamin nucleoskeleton provides a scaffold for the anchoring of highly condensed heterochromatic DNA to the nuclear envelope, thereby establishing the three-dimensional architecture of the genome. Insight into the importance of lamins to cellular viability can be gleaned from laminopathies, severe disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding lamins. A cellular consequence of lamin dysfunction in laminopathies is relaxation of heterochromatic DNA. Similarly, we have recently reported the widespread relaxation of heterochromatin in tauopathies: age-related progressive neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, that are pathologically characterized by aggregates of phosphorylated tau protein in the brain. Here we demonstrate that acquired lamin misregulation though aberrant cytoskeletal-nucleoskeletal coupling promotes relaxation of heterochromatin and neuronal death in an in vivo model of neurodegenerative tauopathy. Genetic manipulation of lamin function significantly modifies neurodegeneration in vivo, demonstrating that lamin pathology plays a causal role in tau-mediated neurotoxicity. We show that lamin dysfunction is conserved in human tauopathy, as super-resolution microscopy reveals a significantly disrupted nuclear lamina in postmortem tissue from human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Our study provides strong evidence that tauopathies are neurodegenerative laminopathies and identifies a new pathway mediating neuronal death in currently untreatable human neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease.

“Lamin Dysfunction Mediates Neurodegeneration in Tauopathies” by Bess Frost, Farah H. Bardai, and Mel B. Feany in Current Biology. Published online December 24 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.039