One of the big challenges with spinal cord injuries is that spinal cord neurons don’t have the ability to regrow after an injury. That’s why most spinal paralysis in patients is permanent.

So scientists tend to focus their research on regrowing peripheral neurons – those that extend from the spinal column to the tips of the hands and feet. Peripheral neurons in the body’s extremities have the ability to regenerate, helping people regain some movement and sensation.

In new research, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a master gene involved in orchestrating the regrowth of peripheral nerves. The gene works as a main switch, making other genes “flip on” in a domino-like fashion. Understanding how these nerves regenerate one day may aid efforts to regrow spinal cord neurons, the researchers said.

The findings are published online Oct. 29 in the journal Neuron.

Surprisingly, senior author Valeria Cavalli, PhD, associate professor of neurobiology, has shown that injury to peripheral nerves flips on a master gene, called hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha, otherwise known as HIF-1alpha. This gene, in turn, activates some 200 genes involved in the regrowth of peripheral nerves.

“What is interesting about HIF-1alpha is that it is known to be sensitive to how much oxygen is in the cell,” said Cavalli. “If the oxygen level is normal, there isn’t much H1F-1alpha, but in stress conditions such as a lack of oxygen, there is more of this gene to protect the cell and organism from this stress. This knowledge gave us the opportunity to use a noninvasive tool to increase the levels of this factor by simply decreasing the levels of oxygen.”

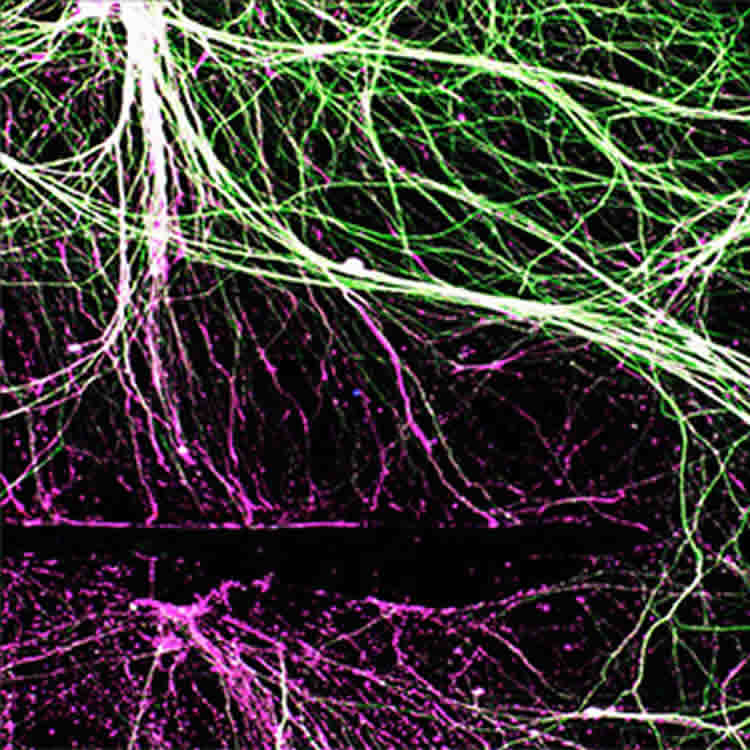

In the lab, Cavalli cultured neurons in a plastic dish and used a zero oxygen environment to measure the regrowth of nerve axons, the branches of nerve cells that transmit nerve signals. In other experiments, the researchers stressed out mice, putting them in 8 percent oxygen environments for 10 minutes, followed by normal air – about 21 percent oxygen – for 10 minutes. They repeated this cycle six times.

What they found was that the “stressed out” neurons responded by growing the nerve axons that connect to the muscle (motor neurons) as well as those that connect to the skin (sensory neurons) much better than those that were not “stressed out” with low oxygen.

“If you remove the oxygen for a little time, the cell thinks ‘I’m so stressed out, I have to do something!’ and starts activating many genes that allow the nerves to start to regrow,” she said.

Doctors already used a similar technique in a study of patients with chronic, incomplete spinal cord injury — patients whose spinal cords are injured but in such a way that some communication between the brain and spinal cord exists, allowing limited feeling and movement. In that study, doctors encouraged recovery of movement by alternating between a 9 percent oxygen environment for 90 seconds and a typical 21 percent oxygen level for 60 seconds, for 15 cycles. The idea was to “stress” the neurons spared by injury and see if that improved their function.

The hope for Cavalli’s team is that the low oxygen environment also may stimulate the damaged neurons to start regenerating and improve recovery.

Cavalli only has seen the nerve axon growth under the microscope. She hopes to keep working to find the right balance and answer the questions: Is less oxygen truly beneficial? What about the time limits? Does functional recovery occur faster and better in mice?

“What we hope, and this is part of our future studies, is that the hypoxia regimen also could wake up the damaged neurons in the spinal cord to start regrowing their axons,” she said.

It was surprising to find the HIF-1alpha at the head of the domino chain, Cavalli said.

“It’s exciting to find something you can use to manipulate neural growth that’s easy and noninvasive like controlling the oxygen environment,” she said. “It could be something we could use to treat nerve injuries and try to get the neurons to start regenerating.”

Funding: The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH): grant numbers DE022000 and NS082446; Hope Center for Neurological Disorders; University of Missouri Spinal Cord Injuries Program; National Research Foundation of Korea; and Wings for Life.

Source: Judy Martin – WUSTL

Image Credit: The image is credited to Cavalli Lab

Original Research: Abstract for “Activating injury-responsive genes with hypoxia enhances axon regeneraion through neuronal HIF-1alpha” by Yongcheol Cho, Jung Eun Shin, Eric Edward Ewan, Young Mi Oh, Wolfgang Pita-Thomas, Valeria Cavalli in Neuron. Published online October 29 2015 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.050

Abstract

Activating injury-responsive genes with hypoxia enhances axon regeneraion through neuronal HIF-1alpha

Highlights

•HIF-1α controls multiple injury-induced genes in sensory neurons

•Conditional knock out of HIF-1α impairs sensory axon regeneration

•The HIF-1α target gene VEGFA contributes to stimulate axon regeneration

•Induction of HIF-1α using hypoxia enhances axon regeneration in sensory neurons

Summary

Injured peripheral neurons successfully activate a proregenerative transcriptional program to enable axon regeneration and functional recovery. How transcriptional regulators coordinate the expression of such program remains unclear. Here we show that hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) controls multiple injury-induced genes in sensory neurons and contribute to the preconditioning lesion effect. Knockdown of HIF-1α in vitro or conditional knock out in vivo impairs sensory axon regeneration. The HIF-1α target gene Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA) is expressed in injured neurons and contributes to stimulate axon regeneration. Induction of HIF-1α using hypoxia enhances axon regeneration in vitro and in vivo in sensory neurons. Hypoxia also stimulates motor neuron regeneration and accelerates neuromuscular junction re-innervation. This study demonstrates that HIF-1α represents a critical transcriptional regulator in regenerating neurons and suggests hypoxia as a tool to stimulate axon regeneration.

“Activating injury-responsive genes with hypoxia enhances axon regeneraion through neuronal HIF-1alpha” by Yongcheol Cho, Jung Eun Shin, Eric Edward Ewan, Young Mi Oh, Wolfgang Pita-Thomas, Valeria Cavalli in Neuron. Published online October 29 2015 doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.050