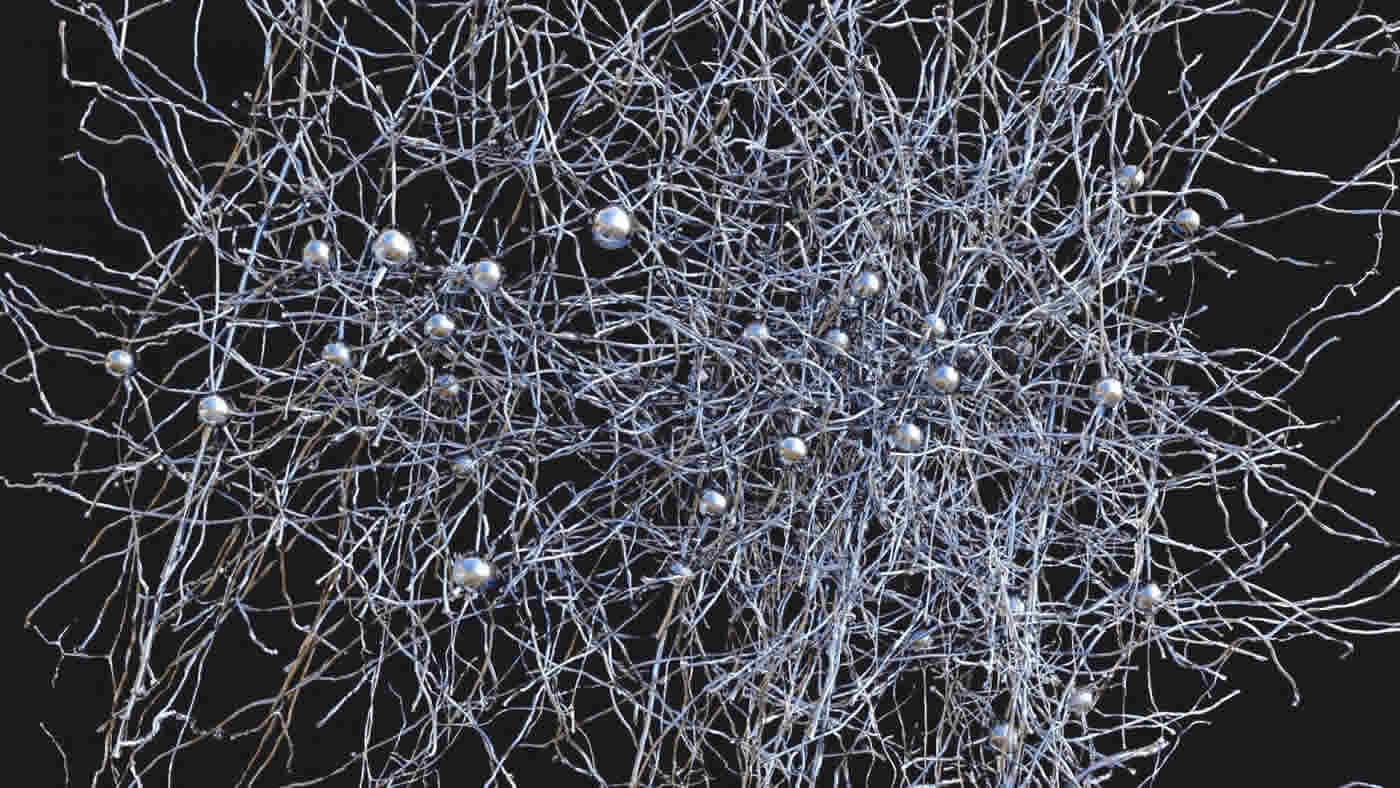

Robust network of connections between neurons performing similar tasks shows fundamentals of how brain circuits are wired.

Even the simplest networks of neurons in the brain are composed of millions of connections, and examining these vast networks is critical to understanding how the brain works. An international team of researchers, led by R. Clay Reid, Wei Chung Allen Lee and Vincent Bonin from the Allen Institute for Brain Science, Harvard Medical School and Neuro-Electronics Research Flanders (NERF), respectively, has published the largest network to date of connections between neurons in the cortex, where high-level processing occurs, and have revealed several crucial elements of how networks in the brain are organized. The results are published this week in the journal Nature.

“This is a culmination of a research program that began almost ten years ago. Brain networks are too large and complex to understand piecemeal, so we used high-throughput techniques to collect huge data sets of brain activity and brain wiring,” says R. Clay Reid, M.D., Ph.D., Senior Investigator at the Allen Institute for Brain Science. “But we are finding that the effort is absolutely worthwhile and that we are learning a tremendous amount about the structure of networks in the brain, and ultimately how the brain’s structure is linked to its function.”

“Although this study is a landmark moment in a substantial chapter of work, it is just the beginning,” says Wei-Chung Lee, Ph.D., Instructor in Neurobiology at Harvard Medicine School and lead author on the paper. “We now have the tools to embark on reverse engineering the brain by discovering relationships between circuit wiring and neuronal and network computations.”

“For decades, researchers have studied brain activity and wiring in isolation, unable to link the two,” says Vincent Bonin, Principal Investigator at Neuro-Electronics Research Flanders. “What we have achieved is to bridge these two realms with unprecedented detail, linking electrical activity in neurons with the nanoscale synaptic connections they make with one another.”

“We have found some of the first anatomical evidence for modular architecture in a cortical network as well as the structural basis for functionally specific connectivity between neurons,” Lee adds. “The approaches we used allowed us to define the organizational principles of neural circuits. We are now poised to discover cortical connectivity motifs, which may act as building blocks for cerebral network function.”

Lee and Bonin began by identifying neurons in the mouse visual cortex that responded to particular visual stimuli, such as vertical or horizontal bars on a screen. Lee then made ultra-thin slices of brain and captured millions of detailed images of those targeted cells and synapses, which were then reconstructed in three dimensions. Teams of annotators on both coasts of the United States simultaneously traced individual neurons through the 3D stacks of images and located connections between individual neurons.

Analyzing this wealth of data yielded several results, including the first direct structural evidence to support the idea that neurons that do similar tasks are more likely to be connected to each other than neurons that carry out different tasks. Furthermore, those connections are larger, despite the fact that they are tangled with many other neurons that perform entirely different functions.

“Part of what makes this study unique is the combination of functional imaging and detailed microscopy,” says Reid. “The microscopic data is of unprecedented scale and detail. We gain some very powerful knowledge by first learning what function a particular neuron performs, and then seeing how it connects with neurons that do similar or dissimilar things.

“It’s like a symphony orchestra with players sitting in random seats,” Reid adds. “If you listen to only a few nearby musicians, it won’t make sense. By listening to everyone, you will understand the music; it actually becomes simpler. If you then ask who each musician is listening to, you might even figure out how they make the music. There’s no conductor, so the orchestra needs to communicate.”

This combination of methods will also be employed in an IARPA contracted project with the Allen Institute for Brain Science, Baylor College of Medicine, and Princeton University, which seeks to scale these methods to a larger segment of brain tissue. The data of the present study is being made available online for other researchers to investigate.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 EY10115, R01 NS075436 and R21 NS085320); through resources provided by the National Resource for Biomedical Supercomputing at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (P41 RR06009) and the National Center for Multiscale Modeling of Biological Systems (P41 GM103712); the Harvard Medical School Vision Core Grant (P30 EY12196); the Bertarelli Foundation; the Edward R. and Anne G. Lefler Center; the Stanley and Theodora Feldberg Fund; Neuro-Electronics Research Flanders (NERF); and the Allen Institute for Brain Science.

Source: Rob Piercy – Allen Institute

Image Source: The image is credited to Clay Reid, Allen Institute; Wei-Chung Lee, Harvard Medical School; Sam Ingersoll, graphic artist.

Original Research: Abstract for “Anatomy and function of an excitatory network in the visual cortex” by Wei-Chung Allen Lee, Vincent Bonin, Michael Reed, Brett J. Graham, Greg Hood, Katie Glattfelder and R. Clay Reid in Nature. Published online March 28 2016 doi:10.1038/nature17192

Abstract

Anatomy and function of an excitatory network in the visual cortex

Circuits in the cerebral cortex consist of thousands of neurons connected by millions of synapses. A precise understanding of these local networks requires relating circuit activity with the underlying network structure. For pyramidal cells in superficial mouse visual cortex (V1), a consensus is emerging that neurons with similar visual response properties excite each other1, 2, 3, 4, 5, but the anatomical basis of this recurrent synaptic network is unknown. Here we combined physiological imaging and large-scale electron microscopy to study an excitatory network in V1. We found that layer 2/3 neurons organized into subnetworks defined by anatomical connectivity, with more connections within than between groups. More specifically, we found that pyramidal neurons with similar orientation selectivity preferentially formed synapses with each other, despite the fact that axons and dendrites of all orientation selectivities pass near (

“Anatomy and function of an excitatory network in the visual cortex” by Wei-Chung Allen Lee, Vincent Bonin, Michael Reed, Brett J. Graham, Greg Hood, Katie Glattfelder and R. Clay Reid in Nature. Published online March 28 2016 doi:10.1038/nature17192