Summary: Modifying genes essential for sensing pheromones in ants resulted in the insects’ displaying deficiencies in social behaviors and reduced ability to survive within a colony.

Source: Rockefeller University.

Ants run a tight ship. They organize themselves into groups with very specific tasks: foraging for food, defending against predators, building tunnels, etc. An enormous amount of coordination and communication is required to accomplish this.

To explore the evolutionary roots of the remarkable system, researchers at The Rockefeller University have created the first genetically altered ants, modifying a gene essential for sensing the pheromones that ants use to communicate. The result, severe deficiencies in the ants’ social behaviors and their ability to survive within a colony, both sheds light on a key facet of social evolution and demonstrates the feasibility and utility of genome editing in ants.

“It was well known that ant language is produced through pheromones, but now we understand a lot more about how pheromones are perceived,” says Daniel Kronauer, head of the Laboratory of Social Evolution and Behavior. “The way ants interact is fundamentally different from how solitary organisms interact, and with these findings we know a bit more about the genetic evolution that enabled ants to create structured societies.”

Social beginnings

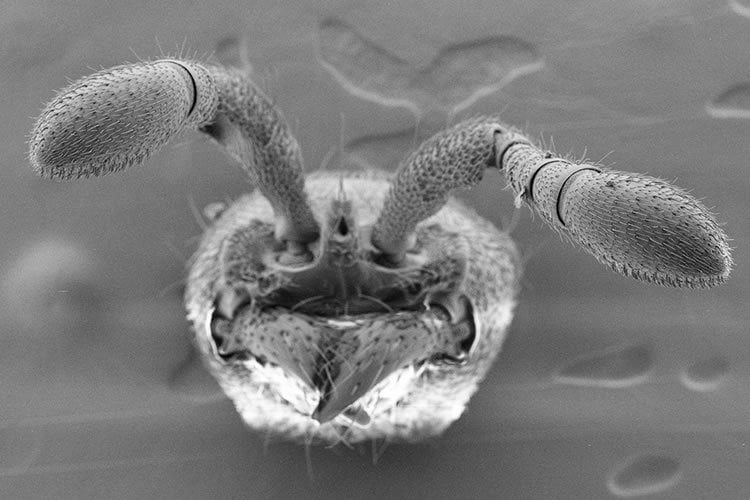

The most important class of pheromones in ant communication are hydrocarbons, which can communicate species, colony, and caste identity as well as reproductive status. These pheromone signals are detected by porous sensory hairs on the ants’ antennae that contain what are called odorant receptors—proteins that recognize specific chemicals and pass the signal up to the brain.

Work in the Kronauer lab, led by graduate student Sean McKenzie and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has shown that a group of odorant receptor genes, known as 9-exon-alpha ORs, are responsible for sensing hydrocarbons in the clonal raider ant species Ooceraea biroi.

McKenzie and his colleagues also examined the genomes of related insects to determine where 9-exon ORs emerged in the evolution of this species, and found that there was an enormous duplication in this gene in a relatively short evolutionary timescale: While the ancestors of bees and ants only had one to three copies of this gene, clonal raider ants have about 180 copies. The massive expansion of 9-exon ORs happened concurrently with the evolution of complex social behavior, suggesting that the duplication of odorant receptor genes was vital to the development of ant communication.

Communication interrupted

To further dissect the role of odorant receptors in ant communication and social behavior, the Kronauer lab disrupted a gene called orco, required for the function of all odorant receptors. Introducing the mutation—using a genetic manipulation technique known as CRISPR—was easy. The challenge was keeping the mutant ants alive.

“We had to convince the colonies to accept the mutants. If the conditions weren’t right, the worker ants would stop caring for larvae and destroy them,” says graduate fellow Waring Trible, who led this portion of the study, published separately in Cell. “Once the ants successfully made it to the adult phase, we noticed a shift in their behavior almost immediately.”

Ants typically travel single-file, sensing the route by detecting pheromones left by the ants in front. Using an automated system that tracks color-coded ants and an algorithm that analyzes movement, the researchers observed that, among other behavioral abnormalities, the mutant ants couldn’t fall in line. The finding suggests that the missing odorant receptors are crucial for pheromone detection, and therefore social organization.

The lack of odorant receptors also changed the shape of the ants’ brains. This was a surprise, says Trible, “because brain anatomy is not affected in orco mutants in other insects, like the fruit fly. Our findings suggest that ants are fundamentally different—they need functional odorant receptors for the brain to develop correctly. This points to how crucial sensing odors is to ants, an ability that may be less important in other insects. ”

Now that the lab is able to generate mutant ants, Kronauer has a bucket list of genes to explore, including those related to the division of labor between groups. “We’ve successfully taken a gene out, and next we’d like to put a gene in. We have a whole new world to explore,” says Kronauer.

Source: Daniel Kronauer – Rockefeller University

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to the researchers.

Original Research: Full open access research for “orco Mutagenesis Causes Loss of Antennal Lobe Glomeruli and Impaired Social Behavior in Ants” by Waring Trible’Correspondence information about the author Waring Trible, Leonora Olivos-Cisneros, Sean K. McKenzie, Jonathan Saragosti, Ni-Chen Chang, Benjamin J. Matthews, Peter R. Oxley, and Daniel J.C. Kronauer in Cell. Published online June 29 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.001

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Rockefeller University “First Mutant Ants Shed Light on Evolution of Social Behavior.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 10 August 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/First Mutant Ants Shed Light on Evolution of Social Behavior/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Rockefeller University (2017, August 10). First Mutant Ants Shed Light on Evolution of Social Behavior. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved August 10, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/First Mutant Ants Shed Light on Evolution of Social Behavior/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Rockefeller University “First Mutant Ants Shed Light on Evolution of Social Behavior.” https://neurosciencenews.com/First Mutant Ants Shed Light on Evolution of Social Behavior/ (accessed August 10, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

orco Mutagenesis Causes Loss of Antennal Lobe Glomeruli and Impaired Social Behavior in Ants

Highlights

•We generated odorant receptor co-receptor (orco) mutants in an ant

•orco mutants did not follow pheromone trails or cluster with other ants

•Mutant ants also had greatly reduced antennal lobes in the brain

•Odorant receptors are essential for the complex organization of ant societies

Summary

Life inside ant colonies is orchestrated with diverse pheromones, but it is not clear how ants perceive these social signals. It has been proposed that pheromone perception in ants evolved via expansions in the numbers of odorant receptors (ORs) and antennal lobe glomeruli. Here, we generate the first mutant lines in the clonal raider ant, Ooceraea biroi, by disrupting orco, a gene required for the function of all ORs. We find that orco mutants exhibit severe deficiencies in social behavior and fitness, suggesting they are unable to perceive pheromones. Surprisingly, unlike in Drosophila melanogaster, orco mutant ants also lack most of the ∼500 antennal lobe glomeruli found in wild-type ants. These results illustrate that ORs are essential for ant social organization and raise the possibility that, similar to mammals, receptor function is required for the development and/or maintenance of the highly complex olfactory processing areas in the ant brain.

“orco Mutagenesis Causes Loss of Antennal Lobe Glomeruli and Impaired Social Behavior in Ants” by Waring Trible’Correspondence information about the author Waring Trible, Leonora Olivos-Cisneros, Sean K. McKenzie, Jonathan Saragosti, Ni-Chen Chang, Benjamin J. Matthews, Peter R. Oxley, and Daniel J.C. Kronauer in Cell. Published online June 29 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.001