Protein regulates neuronal communication by self-association.

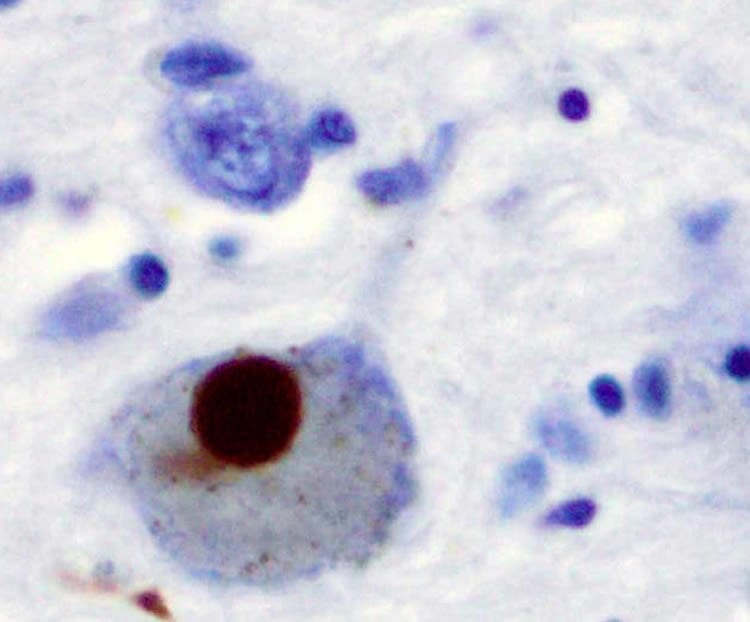

The protein alpha-synuclein is a well-known player in Parkinson’s disease and other related neurological conditions, such as dementia with Lewy bodies. Its normal functions, however, have long remained unknown. An enticing mystery, say researchers, who contend that understanding the normal is critical in resolving the abnormal.

Alpha-synuclein typically resides at presynaptic terminals – the communication hubs of neurons where neurotransmitters are released to other neurons. In previous studies, Subhojit Roy, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine had reported that alpha-synuclein diminishes neurotransmitter release, suppressing communication among neurons. The findings suggested that alpha-synuclein might be a kind of singular brake, helping to prevent unrestricted firing by neurons. Precisely how, though, was a mystery.

Then Harvard University researchers reported in a recent study that alpha-synuclein self-assembles multiple copies of itself inside neurons, upending an earlier notion that the protein worked alone. And in a new paper, published this month in Current Biology, Roy, a cell biologist and neuropathologist in the departments of Pathology and Neurosciences, and co-authors put two and two together, explaining how these aggregates of alpha-synuclein, known as multimers, might actually function normally inside neurons.

First, they confirmed that alpha-synuclein multimers do in fact congregate at synapses, where they help cluster synaptic vesicles and restrict their mobility. Synaptic vesicles are essentially tiny packages created by neurons and filled with neurotransmitters to be released. By clustering these vesicles at the synapse, alpha-synuclein fundamentally restricts neurotransmission. The effect is not unlike a traffic light – slowing traffic down by bunching cars at street corners to regulate the overall flow.

“In normal doses, alpha-synuclein is not a mechanism to impair communication, but rather to manage it. However it’s quite possible that in disease, abnormal elevations of alpha-synuclein levels lead to a heightened suppression of neurotransmission and synaptic toxicity,” said Roy.

“Though this is obviously not the only event contributing to overall disease neuropathology, it might be one of the very first triggers, nudging the synapse to a point of no return. As such, it may be a neuronal event of critical therapeutic relevance.”

Indeed, Roy noted that alpha-synuclein has become a major target for potential drug therapies attempting to reduce or modify its levels and activity.

Co-authors include Lina Wang, Utpal Das and Yong Tang, UCSD; David Scott, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Pamela J. McLean, Mayo Clinic-Jacksonville.

Funding support for this research came from National Institutes of Health (grant P50AG005131-project 2) and the UC San Diego Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Contact: Scott LaFee – UCSD

Source: UCSD press release

Image Source: The image is credited to Marvin 101 and is licensed Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported

Original Research: Abstract for “α-Synuclein Multimers Cluster Synaptic Vesicles and Attenuate Recycling” Sensory Consequences” by Lina Wang, Utpal Das, David A. Scott, Yong Tang, Pamela J. McLean, and Subhojit Roy in Current Biology. Published online September 25 2014 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.027